Pembuka

Manusia telah tiba pada kesimpulan umum yang berlaku lintas zaman, lintas suku-bangsa, lintas wilayah dan lintas kepentingan, bahwa “persatuan adalah kunci sukses”, dan sebaliknya perpecahan ialah jalan menuju kehancuran.

Dalam urusan perjuangan pembebasan bangsa Papua, hal persatuan dan perpecahan telah menjadi isu penting sepanjang sejarahnya. Dan banyak orang mengatakan,

“perpecahan dalam perjuangan Papua Merdeka ialah faktor utama dan pertama yang memperlambat dan bisa-bisa membatalkan perjuangan pembebasan bangsa Papua dan mendirikan Negara West Papua yang merdeka dan berdaulat di luar NKRI”

Ada dua tanggapan terhadap pendapat umum ini. Yang pertama mengatakan, sebenarnya selama ini tidak pernah ada perpecahan dalam perjuangan ini. Bukti pertama karena semua orang Papua memiliki cita-cita yang satu dan sama, tidak ada yang mau tinggal selamanya dengan NKRI atau orang Indonesia. Selama cita-cita bangsa Papua tetap satu, maka tidak ada perpecahan. Kalaupun ada perpecahan, itu kelihatan seperti ada perpecahan, yang berbeda hanyalah cara dan pendekatan, dan tokoh yang satu dengan yang lain, yang belum pernah menyatu menjalankan perjuangan ini. Pendapat kedua mengatakan bahwa memang tidak ada perbedaan atau konflik antara cita-cita orang Papua, akan tetapi para tokoh dan organisasi tidak menyatu, wilayah yang satu dan suku yang satu tidak menyatu, partai atau organisasi yang satu dengan yang lain tidak menyatu. Ini menyebabkan agenda yang satu dengan yang lain tidak menyatu. Maka akibatnya jelas tidak ada persatuan. Masalahnya bukannya ada perpecahan, akan tetapi tidak ada persatuan

- di antara sesama pejuang,

- di antara sesama orang Papua,

- di antara sesama organisasi perjuangan,

- di antara sesama pemimpin perjuangan Papua Merdeka dan

- di antara agenda dan strategi perjuangan Papua Merdeka.

Ada lima “di antara” yang perlu penyelarasan dalam bahasa politik, dan penyatuan dalam bahasa organisasi.

Lalu apakah Kongres Rakyat Papua (KRP) yang selama ini telah diselenggarakan oleh bangsa Papua sebanyak empat (4) kali berhasil mempersatukan dan menyatukan?

KRP I – IV sebagai Momentum Penyatuan untuk Perjuangan Pembebasan

Pada Kongres Rakyat Papua I 1961, tanggal 1 Desember, menyusul sejumlah peristiwa yang telah terjadi beberapa bulan dan tahun sebelumnya, merupakan momentum Deklarasi Kebangsaan Papua, termasuk di dalamnya arah pergerakan bangsa Papua menunju sebuah negara-bangsa modern bernama “Republic of West Papua” atau “West Papua”, sebagaimana tercantum dan tercetak dengan jelas dalam lambang negara West Papua.

Nama bangsa, nama bendera, nama lagu kebangsaan, nama wilayah dan nama negara diproklamirkan pada 1 Desember 1961.

Deklarasi kebangsaan ini disusul dengan janji Belanda sebagai negara penjajah untuk memproklamirkan kemerdekaan bangsa Papua dengan nama Negara West Papua pada tahun 1970, yaitu persis sepuluh (10) tahun setelah pembentukan identitas kebangsaan Papua.

Walaupn begitu, janji Belanda tidak terwujud, pertama-tama karena Belanda tidak bertanggungjawab atas janjinya, dan kedua karena Belanda dipaksa oleh Amerika Serikat atas deal politik dengan NKRI untuk melepaskan wilayah Nederlandch Niuew Guinea kepada Indonesia.

Kongres Rakyat Papua II tahun 2000 di Gedung Olahraga (GOR) Cenderawash Port Numbay adalah peristiwa Deklarasi Kebangkitan bangsa Papua kedua, setelah 40 tahun dihancurkan oleh NKRI, dengan identitas buatan NKRI, satu bangsa, satu bahasa, satu tanah-air: Indonesia. Orang Papua dalam KRP II 2000 memperjelas status dan posisi bangsa Papua di hadapan NKRI dan bangsa-bangsa lain di dunia bahwa bangsa Papua masih tetap pada posisi awal, yaitu hendak mendirikan negara-bangsa sendiri di luar penjajahan, bernama Negara West Papua.

Proses penyatuan kebangsaan kedua ini disusul dengan penyatuan berbagai tokoh dan wilayah yang ada di West Papua, dan juga orang papua yang ada di luar negeri. Orang Papua di Belanda, di Papua New Guinea, di Australia, berdatangan dan mengalami suasana kongres ini.

Kemudian dalam KRP II di lapangan Zakeus, Padang Bulan, Abepura tahun 2011 melangkah lebih maju daripada sekedar kebangkitan kebangsaan Papua, akan tetapi dengan terang-benderang mengumumkan pendirian Negara bernama Negara Federal Republik Papua Barat (NFRPB). Dari sisi sejarahnya sudah sejalan dengang tingkatan atau tahapan perjuangan bangsa Papua, yaitu dari dua kali kebangkitan kebangsaan Papua, kini meningkat menjadi penyatuan negara-bangsa, yaitu Negara Federal Papua Barat.

Hanya satu kritik yang selalu disampaikan oleh kelompok lain ialah bahwa kalau seandainya yang diumumkan ialah Negara Republik West Papua, maka peluang penolakan atau peluang malas atau seolah-olah tidak tahu yang dilakukan oleh kelompok lain yang tidak terlibat waktu itu dapat diminimalisir, dan pelung kleim lebih besar untuk muncul. Dengan memunculkan nama negara baru dan ditambah kata “Federal”, maka banyak diterjemahkan sebagai pembentukan sebuah Negara bagian dari NKRI yang sudah ada.

Penyatuan ini dimentahkan, maka perjuangan terus berlanjut.

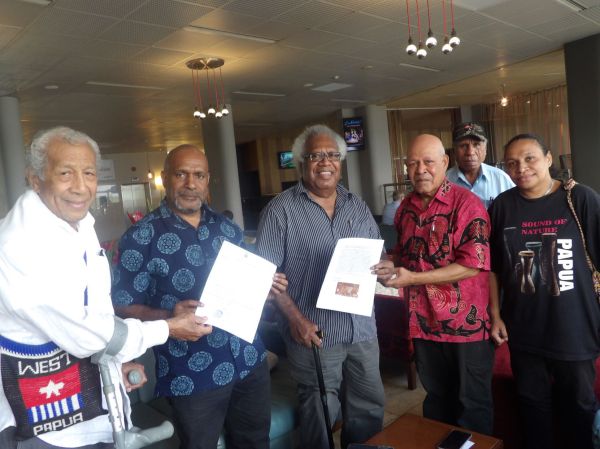

Dalam KRP IV atau Kongres ULMWP I ini terjadi peningkatan, dari sisi tujuan bernegara bangsa Papua. Pada kali ini, telah terjadi peningkatan luarbiasa. Perjuangan bangsa Papua telah memiliki Undang-Undang Dasar, telah memiliki organisasi yang bersatu antara Bitang Satu dan Bintang Empatbelas, antara Republik West Papua dan NFRPB, antara gunung dan pantai. Ini penyatuan yang kuat dan utuh, sesungguh-sungguhnya.

Secara garis besar, telah terjadi kebangkitan bangsa Papua dalam KRP I dan KRP II. Setelah itu dilengkapi dengan kebangkitan negara-bangsa I dalam KRP III 2011 dan dilengkapi dengan kebangkitan negara-bangsa II dalam KRP IV 2023.

Penyatuan sebuah bangsa dan penyatuan sebuah negara-bangsa telah terjadi. Koalisi telah terbangun mantap saat ini.

West Papua telah memiliki Undang-Undang Dasar, yang menjelaskan wilayah dan rayat West Papua secara jelas. West Papua telah memiliki pemerintah yang lengkap dengan kabinet, militer, kepolisian, parlemen dan badan peradilan yang lengkap sebagai sebuah pemerintahan negara-bangsa modern. West Papua telah memiliki lambang kebangsaan, lambang persatuan, dan lembang negara, lagu kebangsaan, dan segala atribut negara-bangsa secara lengkap.

Hanya satu hal yang sedang dinantikan, yaitu aspek pengakuan negara-negara anggota Perserikatan bangsa-bangsa sebagai legitimasi hukum dan politik untuk berbangsa dan bernegara sendiri: duduk sama rendah dan berdiri sama tinggi dengan Indonesia dan negara-bangsa lain di dunia.

Penutup: Bagaimana dengan Konflik Internal ULMWP?

Aktivis, pejuang, tokoh dan organisasi perjuangan pembebasan bangsa Papua seakan tidak pernah terlepas dari penyakit “perpecahan”, yang dalam bahasa politik keren disebut “faksional”, atau terpecah-belah. Sementara itu, kita belajar dalam bangku pendidikan NKRI, terutama oleh guru sejarah mengajarkan mengapa bangsa Indonesia dijajah selama 350 tahun, dan apa yang menyebabkan mereka bisa mereka. Jawabannya adalah karena Belanda menjalankan politik “devide et impera” (adu-domba) dan wajah kemerdekaan Indonesia mulai semakin jelas selelah 28 Oktober 1928 orang Indonesia hadir mendeklarasikan ksetuan bangsa, tanah air dan bahasa.

Dengan dua dasar pemikiran, merujuk ke dalam West Papua dan pengalaman NKRI, maka kita dapat menarik kesimpulan tentang konflik internal ULMWP.

Pertanyaannya, “Kapan konflik internal:

- antara pengurus ULMWP,

- antara orang Papua: aktivis dan tokoh Papua Merdeka;

- antara organisasi perjuangan pembebasan bangsa Papua;

- antara agenda dan pendekatan perjuangan pembebasan

akan berakhir?

maka jawabannya ialah kembali kepada masing-masing pihak,

- pertama kepada pengurus ULMWP sendiri, antara produk KTT II ULMWP dan hasil Kongres I ULMWP;

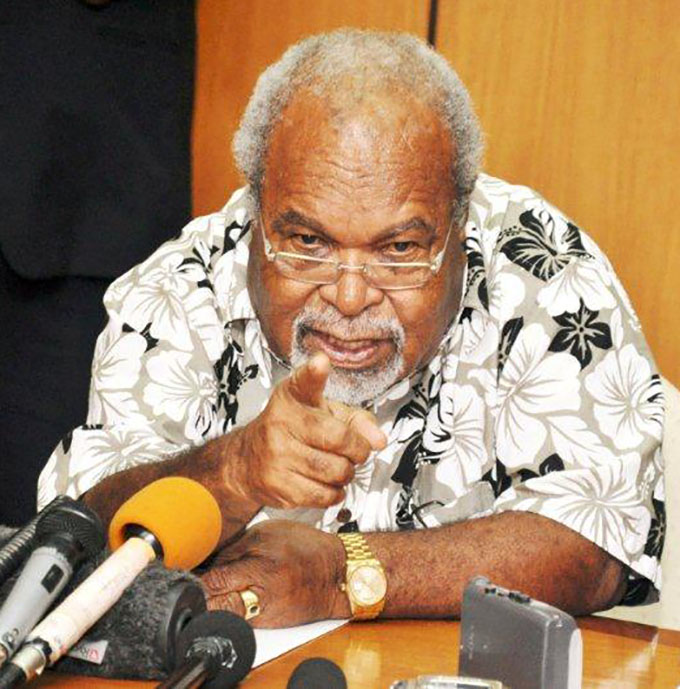

- kedua antara para aktivis dan tokoh Papua Merdeka, terutama Hon. Benny Wenda dan Hon. Octovianus Motte, bersama semua pejabat bersama masing-masing pihak;

- ketiga, antara organisasi WPNCL, PNWP, NFRPB, OPM, KNPB, AMP, DeMMAK, WPNA dan sebagainya;

- keempat, antara agenda dan pendekatan perjuangan yang diajukan masing-masing pihak.

Pertanyaan selanjutnya ialah, “Bagaimana caranya menyatukan semua ini?”

Hanya satu jawabab,

“Hanya pemimpin manapun yang bisa mengundang semua tokoh Papua Merdeka, semua organisasi Papua Merdeka dan semua agenda, pertama-tama dengan segala kerendahan hati, dengan saling menghormati dan menghargai kelebihan dan kekurangan, dengan saling mengakui, duduk sama rendah, berdiri sama tinggi, dari hati ke hati, secara terbuka dan jujur, di antara para tokoh Papua Merdeka, maka semua ini akan berakhir.”

Silakan gunakan alasan legalitas, alasan legitimasi, alasan formalitas, alasan rasional, alasan historis dan alasan lainnya untuk menepuk dada dan mengatakan diri sendiri, kelompok sendiri benar. akan tetapi itu BUKAN caranya menyembuhkan penyakit akut dan mematikan, “perpecahan dalam perjuangan Papua Merdeka”

Silakan gunakan pendekatan ini lebih bagus dan yang lain lebih terkebelakang.

Silakan gunakan dalil yang ini dibuat oleh orang Papua Merdeka dan yang itu dibuat oleh orang moderat binaan NKRI.

Apapun alasannya, kita wajib bergerak menyatukan semuanya. Dengan sekuat-tenaga. Dengan biaya besar. Dengan tekun.

Kalau Indonesia membutuhkan 350 tahun untuk mencapai tujuan, West Papua butuh 3 kali lipat lebih cepat daripada waktu itu.

Vanuatu Dailypos

Vanuatu Dailypos