By Rohan Radheya *

In 1975 when Tan Sen Thay fled his native land Indonesia he arrived in the Netherlands with just two gulden and a traditionally woven West Papuan noken bag.

Traditional accessories from West Papua alongside the outlawed West Papuan independence flag, the Morning Star. Photo: Rohan Radheya

The Chinese Indonesian claimed to Dutch immigration authorities that he was a senior representative of The West Papuan government, a predominantly black elite from a Melanesian province in Indonesiaʼs most Eastern federation.

Their government was on a critical stage waging a poorly equipped rebellion for independence.

“If we do not get Dutch assistance immediately, we will be wiped out,” he warned.

Tan Sen insisted that the Dutch had a moral obligation to help West Papua. After the infamous Trikora incident between the Netherlands and Indonesia in 1961, the Dutch were forced to relinquish Papua under international pressure.

In 1969, West Papua was annexed by Indonesia in a highly criticised referendum known as the Act of Free Choice.

Some 1025 tribal leaders were rounded up to vote for the political status of a population of nearly one million native Papuans while Indonesian soldiers allegedly held entire villages at gunpoint. The participants voted unanimously for Indonesian control.

Serious allegations of human rights violations would follow, including claims of war crimes and genocide committed against indigenous Papuans. Tan Sen and his comrades swore they would not accept the result of the referendum, but would continue battling Indonesia for the fate of the resource-rich island.

The Dutch government realised that by deporting Tan Sen, he would almost certainly be persecuted at return. He was granted political asylum in The Netherlands.

After first setting foot in The Netherlands, Tan Sen started working in an old garage in the Hague, just a few miles away from the Dutch Parliament.

“I then picked the Hague, the seat of the Dutch parliament because the Dutch government had a moral obligation to free my country,” he said.

The garage was a famous hotspot for producing golf cars that were nationally renowned in those days.

As a mechanic Tan Sen earned a minimum wage of 1000 gulden a month (about US$500 at the time) for working 80 hours a week. He would send the majority of his pay back to his comrades in West Papua who were launching sporadic hit and run attacks on Indonesian soldiers from the rugged forests of West Papua.

The remaining money he would wrap in a loin cloth and hide under his pillow while just surviving on simple instant noodles.

“A penny saved is a penny earned, that was my motto,” he said. After toiling for 12 years Tan Sen decided he had saved enough money to open his own gift-shop.

He named it after West Papuaʼs capital Hollandia (now named Jayapura).

His antique gift shop sold everything from imported porcelain statues and rare astrological gem stones to Confucian art paintings and cheap Chinese jewellery.

Money started to flow in and Tan Senʼs hard work began to pay off. He intensified his contributions to the Organisasi Papua Merdeka or OPM ( Free Papua Movement).

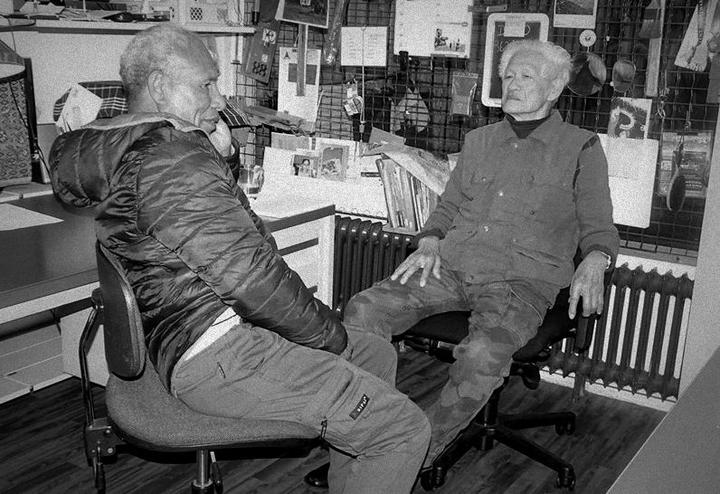

Tan Sen is still living in the Hague today, two blocks away from my home. In spring 2016 when I visited Tan Sen in the Hague he had closed his shop and converted it into his home.

Aged 92 and in perfect health, he had by then already made enough savings to secure his retirement. A wise Confucian who holds some of the best kept secrets to a lost history, Tan is still hoping one day to return to his beloved fatherland.

Warning me not to take photos and to leave my phone in the hall with my shoes, he shows me old documents that ”no one has ever seen”: old black and white photos of West Papuan guerrillas in the 1970’s, transaction data from high profile West Papuan sympathisers around the globe and testimonials from freshly joined recruits worldwide.

“Did you know that during the fall of Soeharto, one of his relatives came to us and offered us $500,000 to purchase arms?” Tan Sen asks.

I’m a little bit sceptical until he shows me records with numbers, dates, and figures relating to a foreign bank account.

He tells me that before he will die, he will send all documents to Leiden University in the Netherlands and sell them for a million euros. The profit will go to his West Papuan wife.

For years Tan Sen designed and weaved handmade uniforms, then smuggled them back to the OPM via refugee camps in areas near the border with PNG.

He would also arrange asylum for West Papuan refugees and finance their trips overseas to help them resettle in countries such as Sweden and Greece.

West Papuans who later took asylum in all corners of Europe had heard about him. In admiration at what he did for West Papua, they would address him as ‘Meneer Tan’ (Lord Tan) or ‘Bapak Tan’ (Father Tan) and send him homemade sago cakes with flowers and gifts.

If anyone wanted to join the independence movement abroad, Tan Sen was the only one mandated by the leadership of the OPM to take their oath of loyalty.

Recruits had to put their right hand on the bible, and smell the outlawed West Papuan morning star flag. If Tan Sen deemed them fit, they could join.

The Quest for Nationhood

Tan Sen Thay was born in Surabaya, Indonesia in a wealthy Chinese family. Growing up as a Chinese Indonesian during the 1965 communist purge by Soeharto, his family fled to West Papua in fear of persecution. His parents were Hokkien transmigrants who migrated to Indonesia from China in search of a better life.

After making generous contributions to Papuan communities, his family soon started to build a respected reputation around The Abepura neighbourhood in West Papuaʼs capital Jayapura. When young Tan Sen saw mass human rights violations committed against West Papuans at the hands of the Indonesian Army, it angered him.

He made a drastic decision. The next day he would depart to the jungles to join the Papuan movement led by a former Papuan-Indonesian Sergeant named Seth Jafeth Rumkorem.

Rumkorem was a young charismatic Papuan officer trained in the Indonesian military academy in Bandung. His father Lukas Rumkorem had been part of a nationalistic Indonesian militia called Barisan Merah Putih. Initially both father and son opened their arms for the Indonesians after Dutch departure.

But after seeing Indonesian cruelty committed against his fellow countrymen, Seth Rumkorem would soon defect and go on to orchestrate a decades-long rebel insurgency from the Papuan jungles against the Indonesian army over the fate of the Western half of New Guinea island.

On 1 July 1971 Rumkorem and his followers gathered in the border areas with PNG. The intention was to boycott Papuan-Indonesian elections. In consultation with Tan Sen and other prominent Papuans, Rumkorem proclaimed a constitution, senate, army, national flag, and anthem.

The proclamation read as follows:

”To all the people of Papua, from Numbai to Merauke, from Sorong to Baliem(Star Mountains) and from Biak to Adi Island. With the help and blessing of God Almighty, we take this opportunity to declare to you all that today, 1 July 1971, the land and people of Papua have been proclaimed to be free and independent (de facto and de jure) May God be with us, and may the world be advised, that the true will of the people of Papua to be free and independent in their own homeland has been met.”

Sink or Swim

Tan Sen was a pious, gentle-mannered introvert with no real experience in war but with his steadfast loyalty and ethnic background he was considered the ultimate propaganda tool by his senior black commanders. Rumkorem appointed him as Minister of Finance in his cabinet.

Tan was asked to travel abroad to lobby for West Papuan independence. With a small delegation Tan Sen set off to London, Senegal and Solomon Islands to muster international support. His fellow comrades under the leadership of Rumkorem would stay fighting from the dense Papuan bush until Tan Sen and co managed to find diplomatic support.

“But without outside help it was impossible,” claimed Louis Nussy, one of Rumkoremʼs most trusted associates, who explained that their small force couldn’t match the Indonesian Army for equipment.

“The Indonesians were supplied by allies such as Russia and the United States. We were just depending on old rusty mouser rifles that we occasionally managed to snatch away from Indonesian soldiers,” he explained.

“There was no ammunition. We would just melt iron in the midst of the jungle,” he said.

Rumkorem and his comrades continued to suffer heavy casualties, and were losing huge terrain on a daily basis. After being pushed out of cities such as Jayapura, Biak and Manokwari, Rumkorem started to realise that it was a ‘sink or swim’ situation. He and his supporters retreated back to the forests while Tan Sen ended up taking asylum in the Netherlands.

Tan ran out of funds to continue his lobby abroad. “Returning would be suicide,” he later testified.

“A chain is only as strong as its weakest link. This was certainly the case in our context,” said Louis Nussy, who is now exiled in Greece.

“We were very efficient in guerrilla tactics but without proper hardware we were facing tough sledding.

“We realised it was just a matter of time before we would be captured or killed,” he explained.

In the meantime with Tan abroad, Rumkorem gained valuable intelligence from fellow independence fighters who had fled to Australia. A cell of West Papuan sympathisers at the highest political level in Vanuatu, were secretly willing to lend weapons and ammunition.

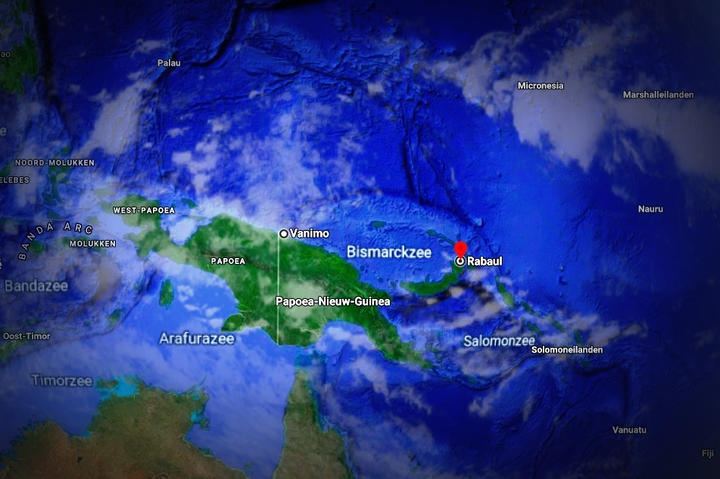

In 1982, Rumkorem decided to leave for the PNG border town of Vanimo to sail to Vanuatu. He was accompanied by eight of his most trusty men.

The plan was straightforward. Rumkorem would leave for arms and return back in a month.

He summoned his intelligence branch PIS (Papua Intelligence Service) and ordered them to obtain accurate weather schedules in PNG waters.

“What Rumkorem did not know was that the head of his intelligence unit had been detained and tortured by the notorious Indonesian special forces Kopassanda,’ʼ said Sonny Saba, one of Rumkoremʼs eight companions.

“In jail he was bribed and given the task to become an informant we would later found out.

“The enemies strategy was clear. Lure away the shepherd and there will just be sheep,” explained Saba, who now lives in exile in PNG.

“Rumkorem knew Indonesian Army tactics inside out, since he was a former Indonesian sergeant.”

“When he was away, the rebels would be a body without a brain,” he said.

The head of Rumkoremʼs intelligence unit then came up with a date just before a devastating storm would strike PNG waters.

Rumkorem left full leadership on the shoulders of his defence minister, Richard Joweni and departed to Vanuatu.

Facing the storm, their prao (traditional Melanesian boat) broke down in the Pacific Ocean and they ended up stranded in Rabaul without food and supplies.

Fearing Indonesian pressure, PNG officials told Rumkorem they could not stay, but they also did not want to extradite them.

In Rabaul, the Papuans met NY Times journalist Colin Campbell. Rumkorem declared to him that his movement sought a revolution, universal human rights, freedom, democracy and social justice.

When asked if it included any Marxist factions, he replied, ”No, our country is a Christian country.”

Betrayal

When Rumkorem eventually realised that there were no weapons in Vanuatu, he called Tan Sen in the Hague.

“Rumkorem was crying, and understood he was tricked,” said Tan Sen. “He told me he wanted to return to West Papua.”

“I told him that I gained valuable intelligence that the Indonesians had sealed the border and were waiting for his return… returning would be suicide.”

“Don’t bite off more than you can chew,” I told him.

“Discredition is the better part of valour and you are no use to us death, I warned him.”

Tan Sen then arranged asylum for Rumkorem in Greece.

From Greece, Rumkorem migrated to the Netherlands from where he continued to lobby for West Papuan independence till his death in 2010, in Wageningen.

Rumkoremʼs departure would be a devastating blow for the remaining West Papuan fighters in the forest who had few or no military experience nor weapons.

Rumkoremʼs successor in West Papua Richard Joweni continued to wage a three-decades long guerrilla insurgency after Rumkoremʼs departure, but he was also no match against the modern weapons of the Indonesian army.

Fearing the death of more of his men, Joweni finally signed a ceasefire with Jakartaʼs special envoy Dr Farid Hussein in 2011, known as the 11-11-11-11 agreement.

The deal was brokered on 11 November 2011, at 11 o’clock at OPM headquarters in the West Papuan jungle.

Dr Hussein earlier also brokered a ceasefire with the independence movement in Aceh in what led to the Helsinki agreement which provided a basis for peace in the restive Indonesian region.

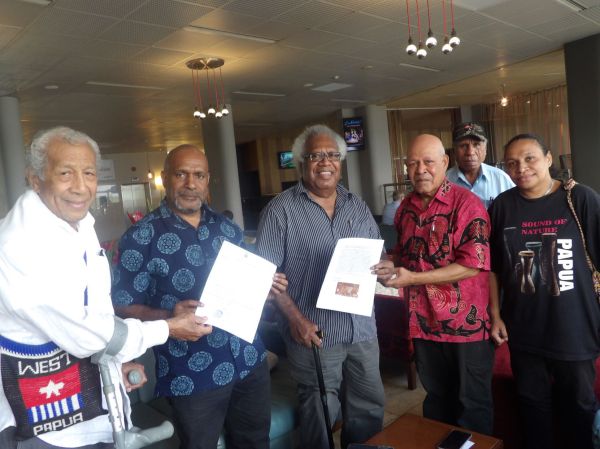

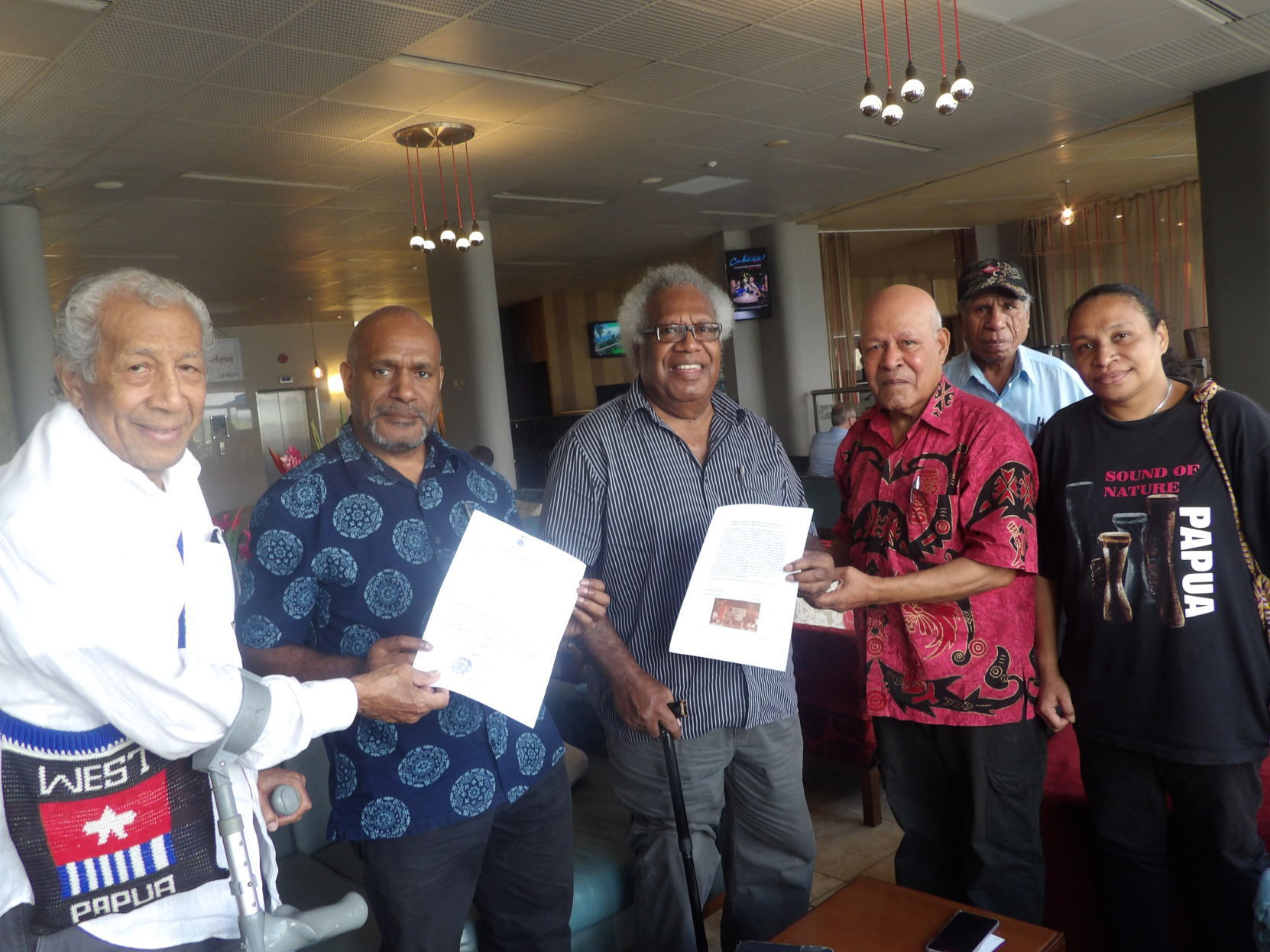

Joweni would later sneak out of West Papua using a fake passport and travel to Vanuatu to meet with Prime Minister Moana Carcasses Kalosil in 2013.

There he would discuss a proposal to lobby for West Papuan membership in the Melanesian Spearhead Group.

After the death of Joweni in 2015, the quest was carried onwards by the United Liberation Movement for West Papua under the stewardship of Andy Ayamiseba, Rex Rumakiek, Octo Mote and others, then eventually taken over by Oxford-based Benny Wenda.

Having attained observer status in the MSG the ULMWP has gained a measure of international recognition that worries Jakarta.

Duct-taped windows

In Tan Sen’s living room hangs several old photos of ancient Confucian war-gods, a religion that was strictly forbidden during Soeharto’s rule.

The living room is decorated with several book closets full of rusty files and old documents. He has pasted all windows with duck tape and builded a fence around the glass in fear of Indonesian spies.

Tan Sen claims the military attache of the Indonesian consulate in the Hague recently paid him a visit.

“He asked for a list of West Papuan independence fighters who lived in exile in The Netherlands,” Tan reveals.

“I would be royally rewarded.”

“What did you do?” I ask curiously.

“What else? I slammed the door at his nose,” he laughs viciously.

Tan Sen doesn’t trust the internet and doesn’t own a smart phone. He doesn’t speak English but is fluent in Dutch.

He reads the full Dutch newspaper in the morning, take notes and then puts the newspaper in his archive. Tan has a full closet of newspapers dating back to 1980.

This pioneering figure in the Papuan independence movement uses an old landline number to occasionally remain in contact with his old comrades in the jungle.

He enquires about the latest developments in the MSG where the ULMWP continued to appeal for full membership.

It is as if the world has passed him by. Most West Papuans do not even know he is alive today.

Even Papuan intellectuals, activists, international journalists, and the young generation of Papuan fighters I met during my trips in West Papua did not know who Tan Sen was.

It has become clear that when the first generation of West Papuan independence fighters fled Papua, they took a huge chunk of Papuan history alongside with them.

The result was that the younger Papuan generation lost a huge part of their own history.

When I ask whether he remains optimistic for West Papuan Independence, Tan Sen says he feels disappointed by the new generation of Papuan independence fighters who don’t deem him fit to lead them any longer.

They would not visit him or include him in the decision making because they felt he was not a native Papuan and not eligible.

“How would you define a Papuan today?” he asks.

“There are tens of thousands of Papuans serving in Indonesian armed forces today.

“They consider themselves Indonesians. Why canʼt I consider myself Papuan Melanesian?

“If race would define your identity or nationality, there wouldn’t be white Africans or black Europeans today,” he explains, citing the plight of white Afrikaners in post independent Zimbabwe.

“What will happen to the millions of Indonesian transmigrants that are born in Papua after 1962 and consider themselves Papuan? ” he stresses.

I remain silent. He pauses before concluding.

“I am still optimistic that I can return to a free and independent West Papua one day,” he shrugs.

*Rohan Radheya is an award-winning filmmaker, documentary photographer and journalist from the Netherlands.

Source: RNZ